Layer-by Layer — Printed Proof:

Case Study: An Out-of-the-Box Solution for a Heavy-Metal Problem at The Schnitz

If you’ve ever been to Portland or at least read about It, you know there are a few iconic images that come to mind—the famous “Portland” marquee is featured in magazines and travel blogs around the world. This bright beacon guides you down Broadway, away from the Square, and beckons you to enter its doors for entertainment and rejuvenation, whether musical, poetic, comedic, or educational.

From the theatre’s website, we learned a little Schnitz history: The building that now houses what locals lovingly call “The Schnitz” was originally the Portland Public Theatre, built in 1928, and later renamed the Paramount Theatre. In 1980, the Portland’5 Center for the Arts became an official part of the Schnitz story. Portland’s then mayor, Connie McCready, appointed a Performing Arts Center Committee (PACC), now known as Portland’5. The newly formed PACC proposed to the City Council that they purchase and renovate the Paramount Theatre. Following initial funding from the city in 1983 and numerous donations from patrons, the theater was beautifully restored. A very generous donation from Portlanders Arlene and Harold Schnitzer was instrumental in the renovation, as the theatre’s current name reflects.

In the Fall of 2013, the Portland'5 name change took place. There had been some confusion previously regarding the name “Portland Center for the Performing Arts,” as it was initially associated with only one venue. The organizational umbrella lost its focus. After 25 years, PCPA wanted to revamp its brand and website. During the many conversations, they had an in-depth discussion about who they are as an organization. The “Portland'5 Centers for the Arts‒ was born, representing the five performance centers and their connection to the City of Roses.

The Problem

Initially built at a different time, updates to the building were inevitable. In the 1920s, lead was a standard metal used to create a wide array of things, including the components found in the house lobby drinking fountains. As we’ve learned since 1928, lead is not suitable for the body, and the City of Portland is opposed to its consumption. (In 2016, the city shared a press release to address finding lead in the fountain’s drinking water.) Portland’5 realized that the Schnitz’s drinking fountains would require a few upgrades.

Images: Wikimedia Commons

Tasked with managing these improvements, Ed Williams is the Facility Manager at Portland’5.

It came down to either finding or fabricating a replacement for the specialized combination water supply and drain fixture used in the front of house lobby drinking fountains. The fountains were original to the 1928 building and only went through cleanup and re-plumbing in 1984 when they renovated the hall.

Replacing these parts would prove to be a challenge best solved by 3D printing.

While changing the lead pipes themselves was a relatively easy fix, changing the components in the bubbler portion of the fountain proved to be more complex. Ed shared his frustrating experience.

I’d searched for the better part of a year, looking for some way to get these parts replicated in lead-free brass. Everything I was coming up with was going to be extremely expensive and/or take months to complete. Every option involved some custom metal casting, machine shop work, etc. I have a strong interest in 3D printing from a technology and hobby standpoint, and I’ve spent a lot of time researching different possible home shop printers.

As the idea of having a part 3D printed came to Ed, he reached out to our team to see if 3D printing could provide the necessary parts.

The Solution

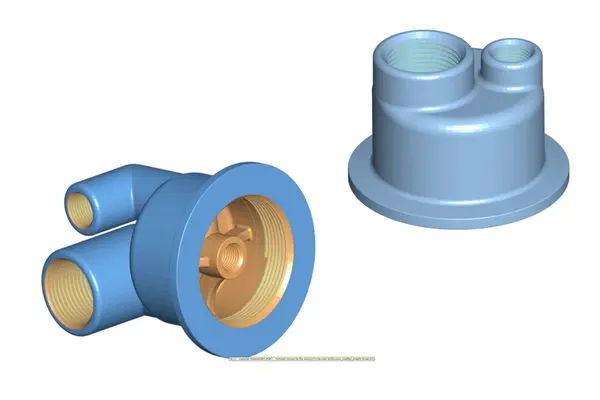

After talking with Ed, our engineers (Chantelle and Ken) and our designer (Bryan) got to work on the new part. In the original metal part, the picture below shows two openings located at the bottom of the piece. The location of the openings complicated things, according to Ed.

Previously, as you can see in the images, the original brass parts had the plumbing ports coming out the bottom, requiring a large brass and copper stack of threaded and sweated parts to connect. In this picture, you can see how tight a fit it is under the fountain bowls for all that piping.

Initially, Ed envisioned replacing just the original piece, which would require creating multiple-part connections. An unintended benefit of going the 3D-printed route was the ability to eliminate this issue, which made Ed happy. Bryan was able to help us out by incorporating the 90-degree bends into the part itself, allowing a much simpler and more compact plumbing connection. We are now using a flexible braided stainless hose to connect, eliminating solder joints. An FDA-approved nylon 12 was used to make the new parts.

With the space being so tight and the replacement cost of the metal part being so exorbitant, the 3D route was much more attractive and viable. Now, to have another part made, Portland’5 will need just three days and less than $90 in materials and finishing. 3D printing offers solutions to problems of all sizes and can even address issues that were previously deemed unsolvable. What problems are you looking to solve? Get in touch with us to see how 3D printing can help!

For more information, please don't hesitate to contact us at or request a quote and upload your file today!